Common name(s)

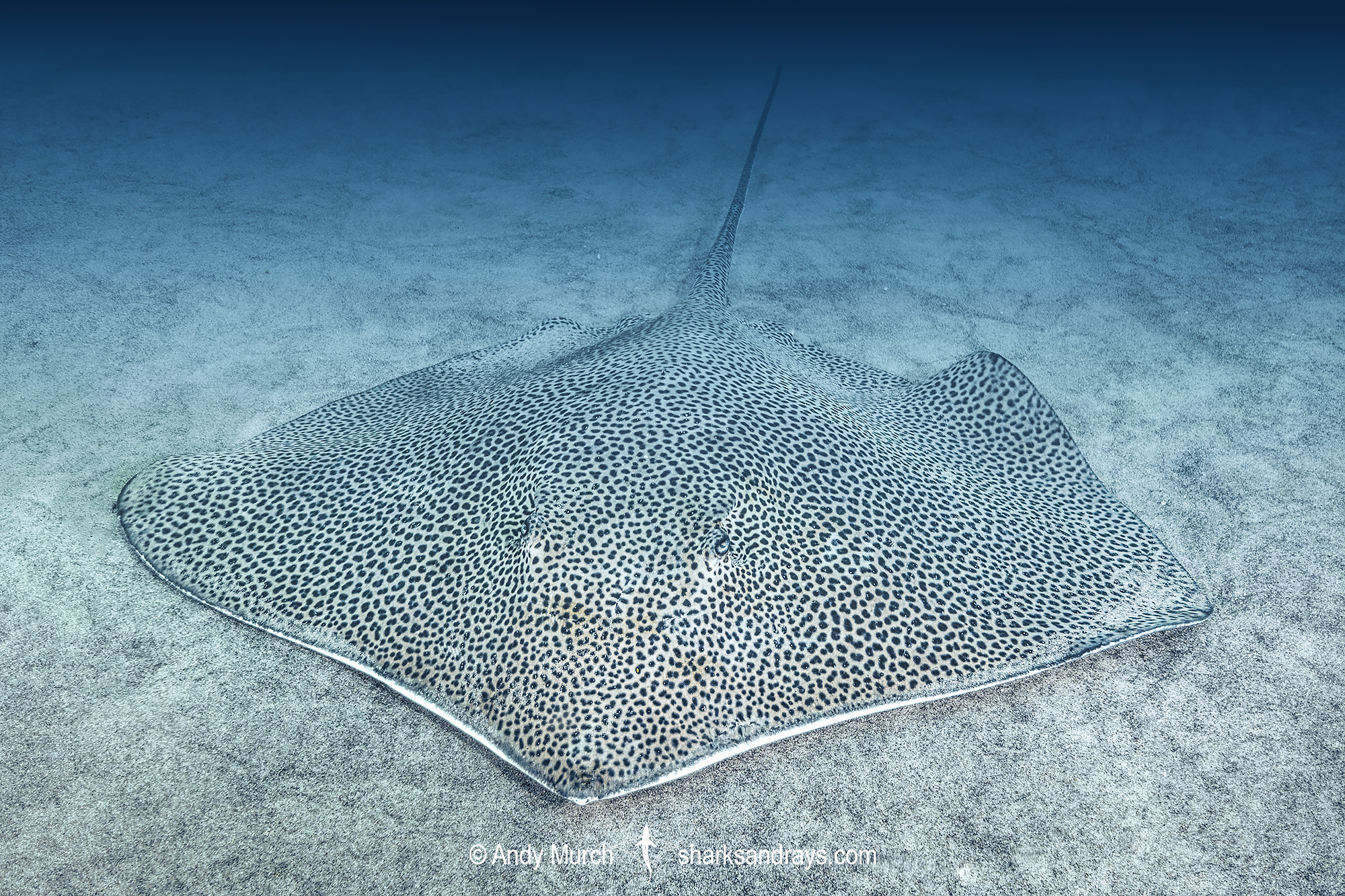

Leopard Whipray.

Identification

A large stingray with a kite-shaped disc that is slightly wider than long. Snout pointed; obtusely angular. Anterior margins of disc concave or almost straight. Pectoral fin apexes narrowly rounded. Pelvic fins short and wide with rounded apexes.

Eyes small and protruding. Snout length 1.8-2.2 x combined eye and spiracle length.

Mouth usually contains 4 oral papillae; 2 in centre and 1 at each side. Weak labial furrows and folds around mouth. Mouth arched. Lower jaw concave at symphysis. Wide, short nasal curtain with a finely fringed margin.

Usually 2 heart shaped thorns on central disc, with up to 13 dermal denticles anteriorly and a row of smaller denticles posteriorly. Well developed denticle band in adults. Tail narrow-based, tapering evenly to caudal sting, then whiplike and filamentous to tip. Tail length (when intact) 2.5-3.7 x disc width. Caudal folds absent. One caudal sting usually present.

Colour

Dorsum whiteish to tan with many dark brown or dark grey spots that form irregular, leopard-like rings. Juveniles usually lighter with large (eye or spiracle sized) black spots. Tail banded beyond sting. Ventrum almost completely white.

Size

Maximum disc width at least 140cm. Disc width at birth approximately 20cm.

Habitat

Sub-tropical/tropical seas. On soft substrates, sometimes adjacent to reefs. From shallow estuaries to at least 70m.

Distribution

Indian Ocean and west Pacific. Found from South Africa, east Africa, Persian Gulf, India, and throughout Southeast Asia from southern Japan to Northern Australia.

Conservation Status

VULNERABLE

The threats to the Leopard Whipray are many of those faced by other Himantura species within its range. However, the Leopard Whipray may be more vulnerable than some of its congeners due to its large size at maturity and maximum size and its preference for inshore coastal waters that are heavily fished and degraded in many parts of its range outside Australian waters (Manjaji and White 2004).

In Indonesia and across large parts of its distribution, the Leopard Whipray is caught by demersal trawl and tangle/gill nets, dropline and longline fishing, Danish seine fishing gear, and coastal artisanal fisheries (Manjaji and White 2004, White et al. 2006). In Southeast Asia, this species is commercially valuable, with most specimens caught as bycatch landed and sold. The Leopard Whipray is important in the gill and tangle net fisheries in Indonesian waters, which likely also includes adjacent waters. These fisheries, along with trawl fishing are particularly intensive in the Arafura Sea region (W. White pers. comm. 2010). In 2004, it was reported that more than 600 trawlers operated in the Arafura Sea and that catches in inshore waters had declined with vessels travelling further south to maintain catches (Manjaji and White 2004). Although the numbers of trawlers currently operating is unclear, this intensive fishing pressure still continues; high levels of Indonesian trawl fishing in the Arafura Sea adjacent to the Australian Fishing Zone have recently been reported (Heazle and Butcher 2007, Northern Territory Government 2009) and thus the level of exploitation of this species could be extremely high.

In recent decades, demersal fishing pressure has increased in both capacity and effort in many areas of this species’ inshore range. For example, demersal resources in the Gulf of Thailand went from being lightly exploited to severely over-exploited between 1973 and 1994 (Pauly et al. 2005). On standardized trawl surveys conducted over this 20 year period in the Gulf of Thailand, the abundance (biomass) of the major trawl bycatch groups was recorded. The group ‘rays’ showed a large reduction in biomass over this period and an ecosystem model fitted to the bycatch data indicated that ‘rays’ were one of the groups most severely impacted by the initial increase in fishing pressure (Pauly et al. 2005). Species-specific catch data are not available, but Indonesian landings of ‘Rays, stingrays, mantas, nei’ (nei = not elsewhere included) increased from ~10,000 t in 1975 to 58,000 t in 2004 (FAO 2009).

This species’ preference for inshore coastal waters means it is also threatened by extensive habitat degradation, including pollution and clearing, and destructive fishing practices. Large coastal areas, in particular mangroves, have been lost in Indonesia and Malaysia through land conversion for urban development, shrimp farms and agriculture. Across Indonesia and Malaysia from 1980 to 2005, the area of mangroves was reduced by >30% (FAO 2007).

Although data are available mostly only for grouped ‘rays’ and not specifically for the Leopard Whipray and/or other Himantura species, given that the Leopard Whipray is a large species with a preference for shallow waters where threats from coastal fisheries and habitat degradation are highest, significant declines are suspected to have occurred in Southeast Asia.

Conversely, this species has refuge from fishing pressure across its range in northern Australia where there is much less fishing pressure and bycatch mitigation measures are enacted. Large specimens were previously occasionally caught as bycatch in the Australian Northern Prawn Fishery (NPF), a trawl fishery across northern Australia, but the introduction of turtle exclusion devices (TEDs) in 2000 significantly reduced the bycatch of this species, particularly those individuals >1 m DW (Brewer et al. 2004). In the NPF, this species was considered to have a moderate to high sustainability to the impacts of trawling (Stobutzki et al. 2002, Zhou and Griffiths 2008). It has also been recorded as a minor component of the bycatch in the banana prawn and scallop sectors of the Queensland East Coast Otter Trawl Fishery (Stobutzki et al. 2001, Courtney et al. 2007), but again the use of TEDs in this fishery should limit bycatch (particularly of larger specimens).

Citation

Rigby, C., Moore, A. & Rowat, D. 2016. Himantura leoparda. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T195456A68628645. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T195456A68628645.en. Downloaded on 15 February 2021.

Reproduction

Matrotrophic aplacental viviparity. Litter size unknown.

Diet

The leopard whipray’s diet is unknown but probably consists of invertebrates and small benthic fishes.

Behavior

Sedentary. Spends much of the day resting on the substrate.

Reaction to divers

Shy but approachable with non-aggressive movements. Generally bolts if approached closely.

Diving logistics

Leopard stingrays are probably encountered at numerous dive sites throughout the Indian Ocean and southeast Asia but divers have a hard time identifying the four spotted himantura species from one another so advice on where to find leopard stingrays is currently unavailable.

The problem of positive identification is exacerbated by the regional use of a variety of common names that are applied to different species in different areas. The following names are sometimes applied to all four himantura species: leopard whipray/stingray, reticulated whipray/stingray, coach whipray, and honeycomb whipray/stingray.

Within the area where leopard whiprays are probably present, at the Ad Dimaniyat Islands off the northeast coast of Oman, rays of the himantura species-complex are apparently abundant (Intel Christophe Chellapermal).

What’s new

View our full list of updates

Similar species

Reticulate Whipray A very similar ray with a sympatric range (unconfirmed in Australia). Distinguished by dense covering of small black spots that do not form leopard-like rings.